JOIN NOW

our Italian Cooking

Newsletter

our Italian Cooking

Newsletter

Publication or use of pictures, recipes, articles, or any other material form my Web site, on or off-line without written permission from the author is prohibited. If you would like to use my articles on your Web site or in your publication, contact me for details. Avoid infringing copyright law and its consequences: read the article 7 Online Copyright Myths by Judith Kallos

Read our

DISCLAIMER and

PRIVACY POLICY

before using

our site

-------------------

Linking Policy

Advertise with us

DISCLAIMER and

PRIVACY POLICY

before using

our site

-

Advertise with us

Copyright © 2003 - 2011 Anna Maria Volpi - All Rights reserved.

Anna Maria's Open Kitchen Site Map

site map

recipes

policies

about us

Some More Hot Topics You'd Like to See adv.

The Island of the Sun

The History of Colorful Sicilian Cooking

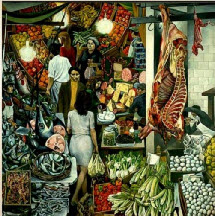

The History of Colorful Sicilian Cooking

La Vucciria, Renato Guttuso, 1974. La Vucciria is an old market in Palermo. The name comes from the French “Boucherie” (“butcher shop”). Guttuso, a famous neo-realist painter, has reproduced the busy ambiance of the most typical of the Mediterranean farmers’ markets in this piece.

Sicilian cooking is undeniably the most complex and colorful in Italy. Like hues on a painter’s palette, the dishes on a Sicilian table represent the various cuisines of the many civilizations that have passed through the island. The longtime isolation of the island and the Sicilians’ innate attachment to tradition have allowed for the preservation and evolution of an elaborate cuisine. In Sicily, new and old and East and West thrive side by side, blending uniquely together like no other place in the world.

Magna Grecia,

al fresco

Early Greek colonizers settled on the seaside from 700 BC to 400 BC and founded most of the coastal cities we know today. For the Greeks, Sicily was a land of legend. The famous Greek poet Homer made Sicily the background for his mythological stories. Mount Etna was home to the god of the underworld, and the island of Vulcano was home to Aeolus, the god in the Odyssey who gifted Ulysses with a sack containing contrary winds.

pitasmaccu

Woodcut map of Sicily, 1548.

‘mpanate (empanadillas)

The seminal moment for Sicilian cooking occurred, however, under Saracen domination. Conquered by the Arabs around 830 AD, Sicily became one of the most splendid Islamic provinces. Palermo, the island’s capital, was an Oriental metropolis, legendary for its luxurious gardens and buildings. The Arabs gave a new face to the gastronomy of the island. They brought in new produce such as peaches, apricots, melons, dates, rice, sugar cane, eggplant, raisins, pistachios, oranges, and lemons, as well as new spices like clove, cinnamon, and saffron.

Under Arab tutelage, the local cuisine acquired the sophisticated flavors that still make it unique one thousand years later. Oriental taste is alive in the many sweet-and-sour dishes, and especially in the desserts, which are extremely sweet and full of honey, almonds, figs, nuts, and pistachios. Many Arabic words transferred to international gastronomic vocabulary, including sorbet, sugar, saffron, and couscous, to mention just a few. It is in Sicily that we have the first testimony of the manufacture of dry pasta, as well as marzipan and nougat. Almost all foods that we think of today as typically Sicilian are typically Saracen.

San Giovanni degli Eremiti (Saint John's of the Hermits), Palermo. The Church built in 1130 for the Benedictine Order is a fine example of Norman-Arab construction. It was built over a mosque in a particularly Arabic style, with five cupolas. The bell tower is distinctively Norman architecture. Were it not for the bell tower, Saint John's could easily be mistaken for a mosque.

At the turn of the millennium, the Normans conquered Sicily for a short but illuminated reign that restored the authority of the Christian church while respecting Arab art and culture.

Comedie Francaisecannolicassata.

Mount Etna during an eruption. Mount Etna near Catania on the East coast of Sicily is one of the most active volcanoes in Italy.

zagara,

Anna Maria Volpi

Anna Maria Volpi

Sicilian cannoli, one of the most famous pastries of the island. A fried crunchy shell is filled with sweetened ricotta cheese and candied fruit.

MENU OF SICILY

Sicilian Recipes

Sicilian Recipes

Involtini di Melanzane

Eggplant Rolls

Eggplant Rolls

Ragu’ di Tonno

Tunafish Ragu

Tomato sauce

Tunafish Ragu

Tomato sauce

Cannoli

Siciliani

Siciliani

Insalata di Arance

e Finocchi

Orange and Fennel Salad

e Finocchi

Orange and Fennel Salad

Pesce Spada alla Siciliana

Swordfish Sicilian Style

Swordfish Sicilian Style